avoiding the laundry list literature review

I’m working in my research methods and thesis prep class on developing research proposals and (at the moment) literature reviews. This is a very helpful example of what to do, and what not to do. Beyond being helpful, it’s just a pleasure to read the craft of writing. I point students to your blog a lot, thanks for the fine work.

I’ve been asked to say more about the laundry list literature review.The laundry list is often called ‘He said, she said” – as one of the most usual forms of the laundry list is when most sentences start with a name. And the laundry list is a problem. It’s hard to read and not very fit for purpose.

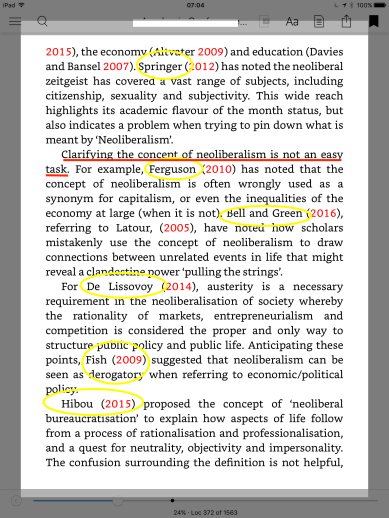

So, what does a laundry list look like? Below is a page of a published book. It is taken from a chapter reviewing the literatures on neoliberalism in ‘the university’. It’s a laundry list. I have:

- underlined in red the sentence where the author says what they are trying to do (you might call this a topic sentence)

- circled the sentences that feature a scholar as the subject of the sentence.

Now let’s see what’s going on in the writing. The second paragraph on the first page begins with the author’s intention…

View original post 1,150 more words

David Berliner, How to get rid of your academic fake-self?

We need a new wave of supportive scholars. #scholarsunday and Raul Pacheco-Vega are good examples http://www.raulpacheco.org/blog/

Some interesting and good advice from David Berliner, How to get rid of your academic fake-self?

Principle of care:

– Substitute a politics of competition by an ethics of care (for yourself and for others). Science is about collaborative knowledge and not a massacre.Principle of incompleteness:

– Acknowledge that you have not read everything and that you cannot debate all topics. Learn to say: “I don’t know anything about Derrida. Maybe one day, I will read him, or not”.Principle of honesty:

– Train yourself to say publicly: “I am not researching anything new at the moment, nor writing”. When a colleague asks you “what are you working on?”, learn to say “I don’t know. I am teaching and that already takes a considerable amount of time. I have nothing to publish right now”.Principle of irony:

– Always have a big critical laugh at metrics and other tricks…

View original post 118 more words

A long strange trip indeed

Now that this amazing chronicle of the Grateful Dead is released and on Amazon streaming, I’ve been thinking about what the Dead have meant to me and in a larger sense regarding music, culture, and creativity. Here’s something I stumbled across in my email; I wrote it in January 2015. Maybe you’ll enjoy it, maybe go watch the Long Strange Trip series…

Subject: Grateful

…for the Dead.

#blacklivesmatter & #nodapl – from UW CBE students

Pleased to see this in my college! Thanks for sharing, Keith.

I’m not sure how long this will last, but it was refreshing to see on Gould Hall this morning. Combined with some recent college-wide interest in helping with Tent City 3, and new courses on race and social justice, CBE is showing a more intense commitment to these critical issues than I’ve seen over the last seven years on campus.

Thoughts on Veterans Day

Family, friends, and friends of friends,

As if the election results are not somber news enough, today is Veterans Day, and with the President elect’s plan to rebuild the military and engage aggressively on numerous fronts we may have more soldiers than ever coming home injured, mentally scarred, or in body bags. I now regularly see young men and women on my campus with prosthetic limbs, evidence of our success in getting them home off the battlefield but not of our ability to find a more peaceful path to engaging with other people on this planet. And it makes me wonder about the wisdom of warfare, and its effects on nations and on people.

My Review of Aitken’s The Ethnopoetics of Space and Transformation: Young People’s Engagement, Activism and Aesthetics

Coming out in Planning Theory. I really liked this book. It was a bit intimidating because it engages a lot of material that I do, or that I should (will). It took me a long time to write, re-read sections of the book, re-draft, etc. Probably waaay too much time, but in the end I’m happy with it and feel like it was worth it. I’ll link the review when it’s put online but for now:

The Ethnopoetics of Space and Transformation: Young People’s Engagement, Activism and Aesthetics by Stuart C. Aitken (2014)

Ashgate Publishing Company

Reviewed by Branden Born, Associate Professor, Department of Urban Design and Planning, University of Washington

One challenge in anchoring critical theory to practice is the balance of the exposition of the theory and the cases or applications that help demonstrate or define it. Writing that tilts too much to the theoretical tends to give glancing attention to on-the-ground experience, and thus such theory may actually explain very little. The theoretical filter can be a coarse one, allowing cases to pass through that might with additional experiential understanding not actually apply. Opposite, an overemphasis on empirical case study may describe in great detail but not adequately explain the theoretical side or how the empirics are tied to a theoretical foundation. The Ethnopoetics of Space and Transformation combines Stuart Aitken’s deep and broad understanding of critical and spatial theory with 30 years of projects from around the world. This book strikes the right balance, and brings to the discussion innovative methods to tell the stories of his chosen participants. In this work, those participants are young people, and Aitken wants us to understand how they can be political agents of change in their social and spatial worlds.

The book unfolds in several phases; Aitken first connects the work of critical spatial theorists to the political potential for societal transformation. In this, he draws on a number of theorists including Ranciere, de Certeau, Deleuze (and Guattari), Agamben, Grosz, Massey, and Zizek. He deftly and selectively pulls connective tissue from them, building his own body that demonstrates the political potential of space as an ingredient or agent of transformative potential for people and places. Once this is established, he adds the voices and experiences of people through the use of the ethnopoetic device.

Ethnopoetry is a methodological technique Aitken developed; here he applies it to earlier ethnographic work and show people and events in new light. This representational method, as he says, “is different from traditional social sciences that rely on theoretical exorcisms, peppered with grey columns of interviewees’ transcribed quotes.” In the ethnopoetic method, Aitken combines photos, diagrams, poetic stanzas, and dialogue to capture not simply what was said, but also how it was said, the emotions that “exceed the text.” This works to a degree, and I found myself simultaneously intrigued and skeptical of the ethnopoetic technique. Granted, this was my first exposure to it, but I am comfortable with standard qualitative methods and quite sympathetic to the need to somehow capture the additional non-conversational elements of such work. As an explanatory tool, it requires a fair amount of faith in the researcher (though the same could be said for a qualitative book form of a case—rarely does an author share with readers the specific details of the method); as a supplemental method to bring richness, depth, and sensitivity it is quite successful.

In each section we delve deeper into forms of, particularly, youth engagement and empowerment in the political sphere through the use of space. Aitken crosses boundaries here both spatially and politically. From the level of the schoolyard—as reflection of the larger society in which it sits—to transnational border communities, to stateless children erased by state bureaucratic manipulation, he demonstrates how young people use, define, and leverage space and society. They do so in a context that almost uniformly works against them. In many ways this makes the use of such a wide range of critical theorists (who generally aren’t examining youth) particularly relevant and new. Questions of agency and ability continually frame young people’s involvement in the functioning of the state and civil society, and in these examples we are forced to reconsider the legitimacy of both arguments against their involvement.

In highlighting the experience of marginalized young people Aitken uses Elizabeth Grosz’s notion of geo-power, which he contextualizes through the lives and experiences of youth and their families. The book examines life events and transformations and the complex engagement these have with the spaces that hold, define, and are defined by them. These transformations are intertwined, undergirded by emotions, and the use of poetry–poetics–is an attempt to capture and explore that easily-lost element. Aitken’s ethnopoetics are derived from interview transcripts, participant observation, and his “experiment with visual and playful methodologies…” If in practice ethnopoetic representations are created through the revisualization of the author of these things, the theoretical underpinnings are primarily post-structural, balancing different Marxist and feminist writers (9).

After laying out an agenda of conceptual exploration and development, giving voice to a particularly marginalized group, and then detailing the use of ethnopoetics, the book turns to several case examples, or vignettes, where we see how youth are taking on activist roles in their communities to make them better, safer, or more just places. These cases–collected over 30 years of experimentation–range from the extremely personal and localized scale to multinational regional studies of development and citizenship. This wide range at first appears rather ambitious—the variety from case to case seemed a little too broad, and some of the chapters feel more natural than others. This is reasonable as Aitken is clear that he is using the ethnopoetic process on cases that were previously conducted using more conventional ethnographic research. However, taken collectively and with Aitken’s narration connecting them while employing his cadre of spatial and development theorists, they work very well to demonstrate the power of affect and activism in these communities. Additionally, as he also mentions, the advancement in spatial theory over that time period allowed for him to bring in this wide variety of theory and theorists. This becomes a good thing for all of us; Aitken believes that better understanding of how space is produced for everyone leads to better understanding of the constitution of justice (12).

This development of understanding of how space is produced for everyone is not a linear one. Space and the work of community in defining it is sometimes done with the state and sometimes done in defiance of the state. Space and its definition is emergent or constantly becoming; here Aitken draws on Agamben and Deleuze (and Guattari) among others to envision multiple ways of being and of becoming. His vignettes demonstrate for the reader many ways of doing both, using young people as agents.

The book is intellectually exciting for its use of theory. Aitken brings together a great group of thinkers that complement each other: filling in holes, addressing weaknesses, and sometimes existing simultaneously in contradiction. As an example, while he relies on Deleuze (and Guattari) extensively, on pages 152-153 Aitken balances their push for innovative and recombinant affects (in this chapter connected to the plight and agency of stateless children) with a critique from Kathy Kirby who suggests that a reliance on post-structuralists like Deleuze and Guattari can lead for a number of reasons to the alteration of the mental space of the subject rather than the real, external world. For those who have also been threading together the likes of Deleuze and Guattari, Agamben, Lefebvre, and Zizek, there will be moments of enlightenment when connections to new or different authors are made. I found the juxtaposition of Grosz’s geo-power with Arturo Escobar’s ideas on development and indigenous voice and Ragnhild Lund’s on people-centered perspective in development theory to be one such satisfying assemblage. Collectively, they represent alternative ways that people can work in contraposition to the state, capitalism, or Zizek’s (Lacan’s) Big Other.

The chapters describing the individual cases are more mixed and different readers will appreciate different cases, or elements of them. One of the challenges with the use of several cases is the time the author needs to spend to set up each so the reader understands the multiple contexts they represent. This for me forced a cyclic ramping up of my knowledge to address each case (I found myself more interested in some than others) and thus an interruption of what had been developing. Ultimately however, the cases are worth the effort and several have stayed in my mind long after I read them.

This book has much to offer academic theorists and applied researchers. For my own work in exploring traditional agricultural and community practices in Oaxaca, Mexico, I found tremendous value in this book. It advances a robust and nuanced theoretical framework that strengthens my own. For example, I struggle with the application of Deleuze and Guattari while simultaneously finding their work inspiring for its relentless push to identify ways of operating that exist outside of the state, and herein I’ve found some useful additional perspective that highlights challenges (Kirby) and new intellectual pathways forward (Escobar). Additionally, as a researcher who leans towards the multiple understandings and descriptions that comprise qualitative work, I am interested in the potential application of ethnopoetry in my own work. It seems to be a valuable tool, especially when working with very different worldviews or cosmologies than the Western rational perspective.

Aitken provides us with a lyrical and near manic paragraph on the final pages of the book in which he ties together in lines and loops some of the key spatial theory he utilizes. This work is not mere summation—it actively connects the theory to the people and places he shares with the reader, and leaves one with a better sense of how young people described throughout must be recognized.

Approaching this book as a planning academic, I couldn’t help but reflect on a story that another planning academic, Kenneth Reardon, uses to demonstrate the importance of listening to and including youth voice. He describes a community design process in which the participants are arranging in a church basement mock elements of a newly-proposed playground for a low-income neighborhood in East St. Louis. A young boy kept positioning a park bench into the space defined as being for a swing set and active playground space. The adults kept moving it back, as these uses were (to them) obviously incompatible. Finally, Reardon asked the boy why he kept moving the bench into that space. The boy replied that for him to play at a playground required his grandmother to be nearby to watch him, and she needed a bench to sit on—without the bench, he couldn’t use the playground. The adults moved the bench back into the playground space. In this robust book, Stuart Aitken gives us many reasons to see young people as similarly impossible to ignore.

a little break

This is an almost always useful blog, and this post is a welcome commentary on work bleeding into the rest of our lives.

Patter is now having a few days off over Christmas, as should you.

But I’ve been taken aback by the volume of things I’ve been sent by people who seem to expect that I will be available to write, revise, review and examine over the Christmas period. I’m not the only one, I know, whose had this experience. It seems to be part of the general pattern of the fast university that being away from the office always equates to being still at work. This is really not acceptable. We all need some down time.

The unwelcome requests are symptomatic of the speeding up/sped-up workplaces that universities have become. Academic time appears to be infinitely elastic, stretching out to contain ever more expectations and tasks. And some of us may be complicit with the need to-fit-everything-in. As Mark Carrigan argues:

- Time-pressure can be a symbol of status and flaunting it can represent one of the few…

View original post 317 more words

Crunch time for academics: tips from Facultydiversity.org

I find these folks have some very solid ideas for faculty productivity generally, and for this season–which can be particularly challenging.

Work Plans for 2015

I’ve had a bunch of irons in the fire lately and need to start documenting, meaning I need to be writing more. This might be the place for the first draft thinking of several projects.

One is an exchange, now completed, of tribal members from Washington State an indigenous community members from Oaxaca, Mexico. A colleague and I applied for university funding to bring four Oaxacans to Washington, and four tribal members to Oaxaca, to discuss issues of food sovereignty, traditional medicinal plant knowledge. The first part happened in September. We just returned from a one-week visit in late December. Both trips went very well. Now the group has been discussing how we continue the work, and perhaps we run a Gathering or something in Cuajimoloyas in 2016.

Another project is an edited volume about food systems, planning, and urban agriculture, in honor of Professor Jerry Kaufman, who passed away January 10, 2013. He was my dissertation advisor, a longtime member of the faculty of the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Wisconsin, and a helluva guy. A mensch in the truest sense. A few of us have been talking about this book project but I need to start moving it forward.

A third is an article, at least, and maybe the drafting of a book, about my developing work merging food sovereignty, planning process, and political theory. There’s a lot going on in my head on this and I think writing in blog form would help give it shape.

Post sabbatical I’ve been able to, for the most part, not get too caught up in so many activities. However, there have been enough to keep me feeling, somewhat paradoxically, unproductive. I’ve been spending some good time on teaching and working on a new undergraduate course, which has been very rewarding. And, the administrivia of the academy could crush a train. Clearer boundaries, more focus, and a better use of my schedule will be key. Stay tuned.